CSP Statement on the Physician-Assisted Death legislation in Canada

The Centre for Suicide Prevention (CSP)

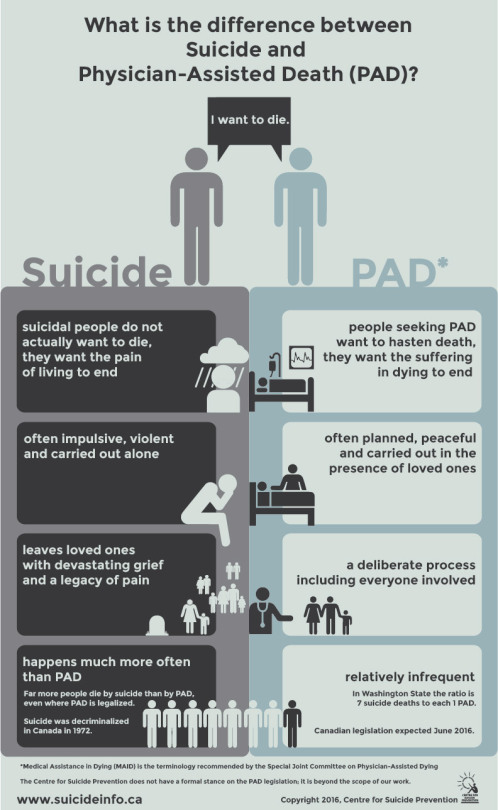

urges the Government of Canada to make a clear distinction between physician-assisted

death (PAD) and suicide. Though often used interchangeably, these are two

different issues that affect two distinct groups of people. It would be

disastrous if, by attempting to help Canadians seeking medical

assistance in dying, Canadians

experiencing suicidality are further stigmatized. Distinguishing between these two

populations with clarity of language is paramount.

Nearly all people who consider,

attempt and/or die by suicide do not want to die: they want the pain of living

to end. When they are at a point of suicidal crisis, they cannot see

alternatives to their situation beyond death. Given help, they will choose

help. Suicidality is temporary: people can be at immediate risk of suicide,

then not, then experience a suicide crisis again. Others may only have one

suicidal experience in their lifetime. With appropriate mental health care,

people who have experienced suicidality can go on to live mentally healthy

lives: recovery is possible. Others learn how to live with their suicidality,

often with the support of others around them.

Far more people die by suicide than

by medical assistance in dying even

where PAD is legalized. In Washington, for example, the ratio of

physician-assisted deaths to suicide deaths is roughly 1:7.

As part of the implementation of physician-assisted

death legislation, CSP urges the Government of Canada to educate Canadians

about the distinction between these two groups to help protect those people

experiencing suicidality. People experiencing suicidality often do not seek

help even though they want it. If death becomes a normalized option, Canadians

may become less knowledgeable, sensitive and likely to help those in need.

Infographic References

American Association of Suicidology. USA. Suicide: 2013 Official Final Data. Retrieved from http://www.suicidology.org/portals/14/docs/resources/factsheets/2013datapgsv2alt.pdf

Brody, H. (1995). Physician-assisted suicide: Family issues.

Michigan Family Review, 1(1), 19-28.

de Groot, M., et al. (2007). Cognitive behaviour therapy to prevent

complicated grief among relatives and spouses bereaved by suicide: Cluster

randomized trial. BMJ. DOI:

10.1136/bmj.39161.457431.55

Giner, et al. (2013). Violent and serious suicide attempters: One

step closer to suicide? Journal of

Clinical Psychiatry, 75(3).

Gvion, et al. (2015). On the

role of impulsivity and decision-making in suicidal behavior. World Journal of Psychiatry, 5(3),

255-259.

Jimenez-Trevino, L. (2015). Factors associated with hospitalization

after suicide spectrum behaviors: Results from multicenter study in Spain. Archives of Suicide Research, 19(1),

17-34.

Loy, M. and Boelk, A. (2014). Losing

a parent to suicide: Using lived experiences to inform bereavement counseling.

New York: Routledge.

Shneidman. E. (1993). Suicide as psychache: A clinical approach to

self-destructive behavior. Northvale, NJ.: Jason Aronson, Inc.

Washington State Department of Health. (2014). 2014 Death with

Dignity Act Report: Executive Summary. Retrieved from http://www.doh.wa.gov/portals/1/Documents/Pubs/422-109-DeathWithDignityAct2014.pdf